Smart Governance

SafeSwim

Auckland City, New Zealand

Background & Urban Challenges

Aucklanders expect to be able to swim and play in the clean water and safe beaches. Auckland's beaches are central to the region's image both nationally and internationally.

Despite the importance Aucklanders place on clean, safe, healthy water, Auckland's beaches suffer from poor water quality from time to time, especially after heavy rain events in areas serviced by aging network infrastructure in the city center and aging onsite septic systems on the urban periphery.

The persistent and lingering nature of this issue has fostered public frustration. There is a strong public desire for corrective action to improve the performance of Auckland's water management network and increase the resilience of the region's infrastructure.

Objectives

Auckland's mayor has proposed significant increases to the level of funding available for water management (including through the introduction of a targeted rate) and supported revisions to the Auckland Plan, to ensure that Auckland 'restores its environment as it grows', 'accounts fully for the past and future impacts of growth' and 'adapts effectively to a changing water future'.

One specific aim is to ensure that Auckland's beaches meet water quality guidelines for safe swimming at least 95% of the time.

Solution Descriptions

In late 2016, Auckland Council commissioned an independent review of its beach bathing water quality monitoring and reporting programme - 'Safeswim'. This review identified issues with the design and delivery of the programme - issues that created a public health risk and perpetuated a false sense of security about the health and safety of Auckland's beaches.

Knowing that issues with the design and operation of the Safeswim programme created a risk of poor public health outcomes, council staff took the view that it was prudent to act quickly to revise the programme ahead of the upcoming summer swimming season - persisting with the old system when it was evident it routinely failed to identify exceedances of guidelines for fecal indicator bacteria was considered untenable.

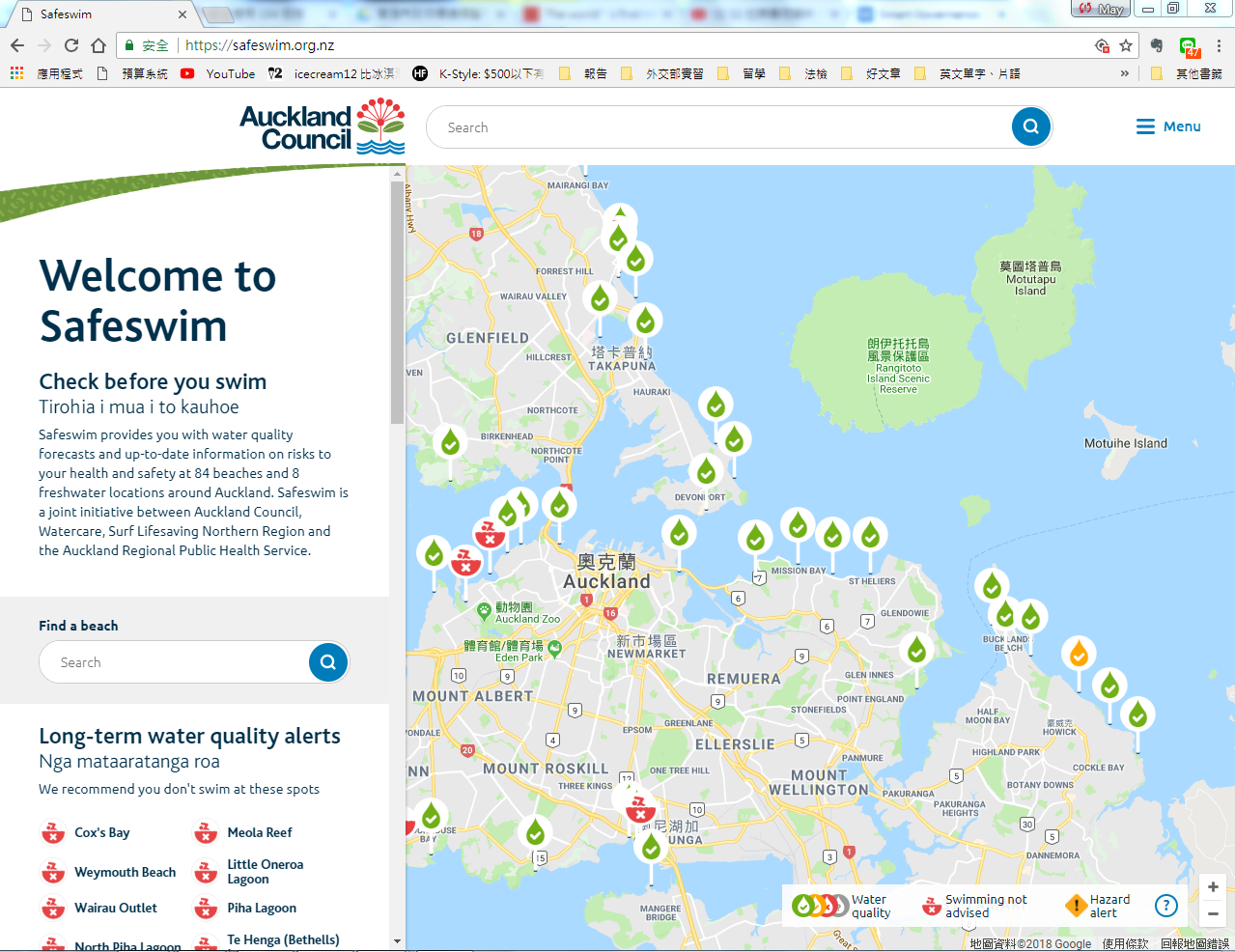

From February to November 2017, Auckland Council and Watercare worked in partnership with Surf Life Saving Northern Region and the Auckland Regional Public Health Service to upgrade the 'Safeswim' programme. Safeswim now provides a fully-integrated web and digital sign platform of advice for beach users, allowing them to 'check before they swim' and make informed decisions about when and where to swim.

Safeswim now combines real-time data on the performance of the wastewater and stormwater networks with predictive models, underpinned by validation sampling, to provide forecasts of water quality at 92 swimming sites around the Auckland region. The water quality predictions take into account rain intensity, duration and location, as well as the tide, wind speed and direction and sunlight. Data from rain gauges around the region a fed into the system to ensure the current prediction reflects actual/observed rainfall. Water quality predictions are automatically overridden if sensors - at pump stations and Engineered Overflow Points on the wastewater network and at key points on the stormwater network - detect overflows that are likely to cause a public health risk at the time when models hadn't predicted poor water quality.

Water quality information is complemented by advice from Surf Life Saving Northern Region and the Auckland Regional Public Health Service on other safety hazards (e.g. dangerous wind and wave conditions, rip currents and the presence of hazardous marine life). Credentialed users from these organizations are able to manually upload public advisory notices, alerting the public to hazards such as dangerous wind or wave conditions, rip currents, jellyfish swarms or shark sightings.

The safeswim.org.nz website is the primary channel in the Safeswim programme for communicating information to the public, but physical signage is also an important part of the programme.

Between two and eight 'static' signs have been installed at the main approach points to all the beaches in the programme. These signs prompt people to 'check before you swim' and point people to the Safeswim website.

'Dynamic' signs are being used at the 11 beaches across the region patrolled by surf lifesavers. These signs have a movable arrow that surf lifesavers set to match the current status of water quality on safeswim.org.nz.

The programme is trialing digital signs at three beaches around the region. The digital signs provide close to real-time information (refreshing every 15 minutes) and reflect what is shown on safeswim.org.nz.

In a large organization like Auckland Council the process of planning and designing large-scale cross-cutting programmes like Safeswim can take years - and years more can elapse before they are implemented.

In this case, the project team gained approval to begin work on 14 February 2017 and had a deadline of 1 November 2017 for implementing a fully-revised programme.

An innovative approach to project management and governance was called for. The council responded by forming a virtual team incorporating members from across all the departments and organizations affected by, and with an interest in, the programme. Programme leadership was allocated to staff seconded to the Safeswim programme (rather than reporting to a 'home team') who were given the mandate to operate across silos and the performance target of delivering a fully-functioning platform on time and within budget.

From the outset, it was clear that parties outside of council had to be involved in the design and delivery of Safeswim if the project was to be a success. Water quality is important, but it is a subset of safety and other agencies have roles in ensuring the safety of Auckland's beaches. Similarly, Auckland Council can take samples that establish the environmental state but translating these findings into statements regarding public health or making judgments that relate to project health needed to be made by the relevant public health agencies.

At the very beginning of the project, team members approached Surf Life Saving Northern Region, the Auckland Regional Public Health Service, Watercare and the region's Mana Whenua (Maori tribes with authority in the region) to explain Safeswim's objectives, outline its general direction and invite participation.

Members of these organizations were integrated into the programme in roles that matched their self-determined interests and resourcing. As the programme began to take shape and where significant decisions on programme direction were required, these partners were invited to step into governance and steering roles.

Project governance was provided by senior members of each contributing department and partner agency. As the programme took shape and began to approach launch, the membership of the programme steering group was expanded to formally include representatives of external partners and the region's Mana Whenua.

The virtual team met fortnightly to agree on tasks that needed to be achieved by the following fortnight, report on progress and find solutions to any barriers that had prevented achievement of tasks in the previous 'sprint'. These meetings helped ensure horizontal integration across the project's workstreams.

At each fortnightly meeting, workstream leaders presented the current status of their work package and the team collectively offered suggestions on how to improve the work package and integrate it with other aspects of the project to achieve overall coherence and integration. This avoided the risk of project components failing to integrate effectively at the back-end of the project and created opportunities for project team members to provide insights outside their area of expertise - 'outsiders' and 'non-experts' can often see problems more clearly than those embroiled in the detail of an area they know extremely well. Throughout this process, staff from the partner agencies were invited to review and assess the solutions being developed by the project team.

Result & Reflections

Safeswim now provides a fully-integrated web and signage platform of advice for beach users, allowing them to 'check before they swim' and make informed decisions about when and where to swim.

Auckland beach users now have access to real-time data on the performance of the wastewater and stormwater networks, and are able to see forecasts of water quality underpinned by predictive models. These forecasts are automatically overridden if sensors detect unpredicted overflows that are likely to cause a public health risk, and additional beach-specific warnings are uploaded if Surf Life Saving Northern Region or the Auckland Regional Public Health Service identify other safety hazards (ie dangerous wind and wave conditions, rip currents and the presence of hazardous marine life).

The Safeswim website has attracted over 130,000 unique users since its launch, and gained nearly 300,000 hits. The interface is performing well and we're receiving feedback that it is easy to access, easy to use and informative. Usage rates continue to grow.

Taking into account monitored overflows, the Safeswim alerts (incorporating model predictions and overflow monitoring) for exemplar validation sites indicate that models are accurately identifying between 67% and 86% of exceedances, meeting performance standards published by the USGS (50%) and comparing well with the previous monitoring programme (4%).

Safeswim was promoted in a recent independent 'value for money' review conducted under section 17A of the Local Government Act, as an exemplar of the kind of cross-agency, cross-department projects necessary to deliver value to Aucklanders. The picture of water quality at Auckland's beaches revealed by Safeswim was used by the Mayor as evidence in support of his proposal to allocate an additional budget in the next Long Term Plan towards lifting water quality at Auckland's beaches and streams.

Despite it being in place as a branded programme since 2010, no one at Surf Life Saving had heard of Safeswim before the project team reached out to them. Now Safeswim is an integrated water quality and beach safety programme providing surf lifesavers with a highly effective platform for providing public advice on beach safety - allowing them to upload warnings about dangerous wind and wave conditions, rip currents and marine life. Safeswim is partnering with Surf Life Saving Northern Region to trial a 'virtual lifeguard' system for providing 'push notifications' to beach users about current hazards, and a system for matching lifeguards and equipment to demand.

The Auckland Regional Public Health Service is working with members of the Safeswim project team to coordinate datasets to help establish whether an observed and previously unexplained spike in cases of gastroenteritis and cryptosporidium following summer storms could be attributed to water quality and Auckland's beaches.

The Safeswim models and validation sampling programme are being used to evaluate the impact of possible alternative management interventions, and to inform business cases for public investment.

In the future, to achieve this level of impact so rapidly the Safeswim project team had to overcome:

A natural and logical desire to integrate Safeswim within existing workstreams and use in-house resources to develop and implement the upgrade. This would have required the project team to work within very tight resource constraints - constraints that would have challenged the project team's ability to meet the delivery deadline and react in an agile and timely way to issues and opportunities that cropped up as the project proceeded.

A natural and understandable tendency to view Safeswim's transparency as a risk, given it would be revealing that water quality at Auckland's beaches was worse than previously thought.

The inevitable gaps between departments in a large bureaucracy and across organizations with responsibilities for water quality and beach safety - each having their own organizational culture in relation to risk-management and decision-making.

Factors critical to success were:

The establishment of a virtual team, led by people who are responsible for the objectives of the project rather than the objectives of their home team. This allowed the project team to keep returning to the overarching objective of improving the region's water quality and avoid being 'trapped' by the status quo.

The willingness of council managers to view this project as a prototype. This allowed the project team to build bespoke systems and trial solutions as the project moved through its phases. Now the revised platform is up and running, council units are working with project team members to integrate the project's operational requirements with their long-term work programmes. This transition is made easier by the presence of project team members who have rotated back to their 'home' teams, bringing with them an intimate knowledge of the project's objective and mechanics.

The emphasis placed on engaging early with politicians and Mana Whenua representatives, and on building relationships with leaders of partner agencies. Giving these parties time to understand the programme fostered well-informed political debate and governance, and allowed the council to build the public/private partnerships necessary to ensure Safeswim is resilient to contextual change.

Having a clear outcome to focus on. It can be difficult to work across a large organization like Auckland Council as each department has its own, entirely legitimate, objectives and processes. In this case, the complexity was multiplied by having to work across different agencies. A clear outcome-focused objective, even if it is some distance away, helped the project team keep people directly and indirectly involved with the project-oriented towards the outcome. At certain times in the project it was a great help to be able to ask how a particular action or position was going to help the project improve water quality and safety at Auckland's beaches.

Avoiding falling into the trap of trying to do too much. As a project gains momentum it is very easy for it to generate ideas, or for people to see how their ideas could be complementary. This tendency to expand needs to be carefully managed to ensure delivery of key objectives

To avoid the trap of trying to do too much (and consequently failing to do anything), the project team borrowed the software development concept of MVP - minimum viable product - and stuck to delivering the minimum possible to deliver a fully-functional product within the timeframe and budget available. If new requirements or good ideas surfaced through the process, they were added to a backlog and evaluated against a set of project priorities. If they were judged to be a priority they were added to the programme and another task was dropped off to make way. Sticking to this discipline is easier said than done. The project steering group's commitment to continual improvement helped - if someone's idea or action dropped down or didn't make it on to the priority list, it could be picked up in subsequent cycles of the programme.

Auckland Council plans to extend the scope of the programme to include additional contaminants (ie heavy metals), and to add more freshwater sites. Surf Life Saving Northern Region is investigating the potential to develop a predictive model for rip currents.

Visit Website: https://ourauckland.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz/articles/news/2017/11/safeswim-jump-online-before-jumping-in/